Heat waves kill more people in the U.S. than hurricanes, tornados, floods, or any other weather hazard—combined. Heat waves have grown three times as long over the last half century and occur twice as often. If we could see these invisible heat waves, they’d look a whole lot more like heat tsunamis.

The good news is that the same policies we need to fight climate-disrupted heat events can also bring us cooling relief. If we design new policies right, our homes and buildings can both cool people inside and stop polluting the air outside. In particular: zero-emission buildings that use clean electric heat pumps bring our dual climate and equity goals (more on those below) within reach. To address both goals, however, we must reimagine the objectives of our energy policies.

Historically, energy policies have operated in a world that was hyper-focused on therms and kilowatt hours, rates, and revenues. Yet, this historic system and its mountain of assumptions is leaving people dying in the cold in one season while dying from heat in the other. Our energy system not only fails to maintain health; its dollars-and-cents assumptions don’t add up at the end of the day. Just last winter, the federal government had to shell out another $5 billion to cover revenues to energy companies so that people could have some basic heating in the face of spiking fossil-fuel prices. But that was just an additional $5 billion for the fossil-fuel prices; we routinely bail out a broken heating regulatory system to the tune of $4 billion annually. Once we expand our lens to include the human reality of our energy policies, we can discover more durable paths forward on both the human and technocratic bases.

Take summertime cooling relief: If we switch from one-way air conditioners that only provide cooling (and that are paired with gas furnaces for heat), to a single device—the all-electric heat pump—that both cools and heats a home, we can make affordability and climate progress at the same time. For example, households in Oregon would save over $150 per year if they switched entirely to heat pumps, adding up to savings of more than $1 billion statewide. And that’s in line with the national average of saving $169 per year from replacing one-way air-conditioners with these two-way heat pumps. But we need to be intentional about how we roll out solutions. Bringing cooling relief first and affordably to historically marginalized communities will not happen without centering climate resilience in equity.

A good example: In 2022, Elevate Energy, an EF grantee, worked with Develop Detroit to upgrade its West Boston Apartment Complex, a multi-family affordable housing building in Detroit. From Elevate:

“West Boston Apartments was heated with a natural gas steam boiler that was causing considerable moisture damage in the basement and needed to be replaced. Elevate removed the failed steam boiler and radiators that were heating seven units of the building, and replaced it with in-unit ductless mini-split heat pumps and thermostats. The replacement is expected to reduce between 16 and 19 tons of carbon emissions a year, about the same emissions from eight single-family homes’ energy use. In addition to being highly efficient, heat pumps also offer both heating and cooling for added comfort for the residents at West Boston Apartments who didn’t have central air conditioning before.”

Another good example is the City of Portland, Oregon’s Heat Response Program, which funds local environmental-justice organizations to provide portable electric heat pumps or cooling units to low-income and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) residents in need. The organizations install heat pumps for people who otherwise would face health and/or financial crises due to extreme heat, and who have been left behind by current policies around heating and cooling.

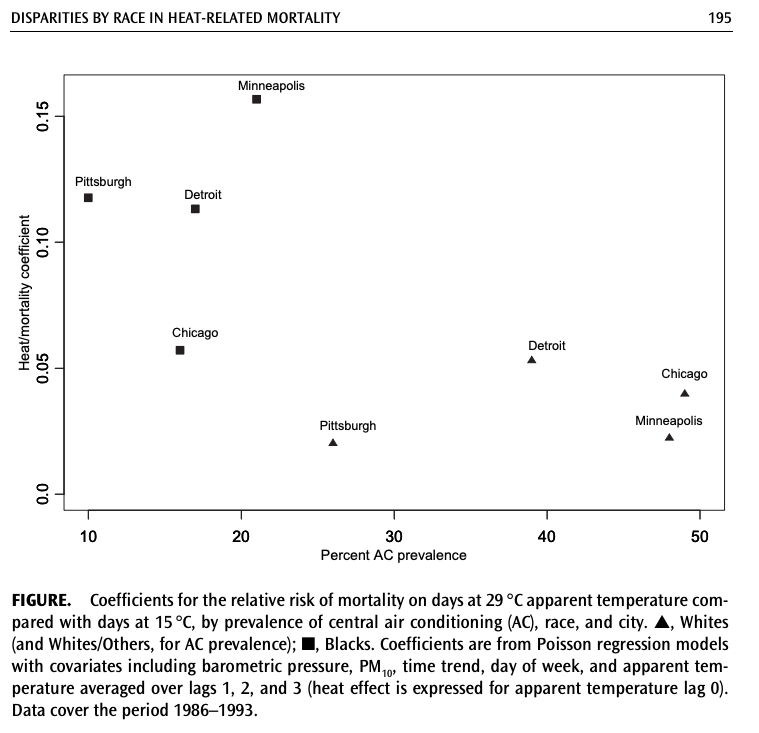

Without advocates’ interventions, market forces for air conditioning alone exacerbate the equity crisis. Historically, the air conditioning market has underserved Black people relative to White people, with significant documented disparities by race. And because of that, Black people die at higher rates during heat waves. The presence of central air-conditioning explains the majority of the difference in heat-associated mortality between Black and White people. See the differences in the same four cities below, split between Black and White households.

Now, if this graph looks gray and dated, that’s because it is. The data are from late last century. Fast-forward over the intervening decades that comprise most of my life: Black and Latine households are still far more likely to lack access to air conditioning. Today, lack of air-conditioning rates in communities of color are double, triple, or even quadruple that of White communities around major metro areas. Fortunately, there are many models that we can improve upon from around the country to ensure disadvantaged communities are able to adopt efficient heat pump and building electrification technologies earlier on the adoption curve.

While our topic focuses on cooling relief, it’s also a window into the larger energy issues we need to solve: More than a quarter of us (27 percent of Americans) have trouble paying our energy bills or have to keep our homes at unsafe temperatures to make ends meet. And there, too, our energy regulatory system has failed Black and Latine communities at about double the rate: Around half of our Black and Brown families are saddled with energy insecurity.

The list of solutions may be long: shutoff moratoria, federal assistance programs, deferred maintenance, efficiency and fuel switching programs, affordable housing policies that provide for cooling, and more. But a central issue is common: When we marry our human-centered goals with our climate goals, we create a more durable path forward. By widening our aperture for solutions, we can better address the bigger picture. And we are grateful to the accomplished network of advocates making that possible.